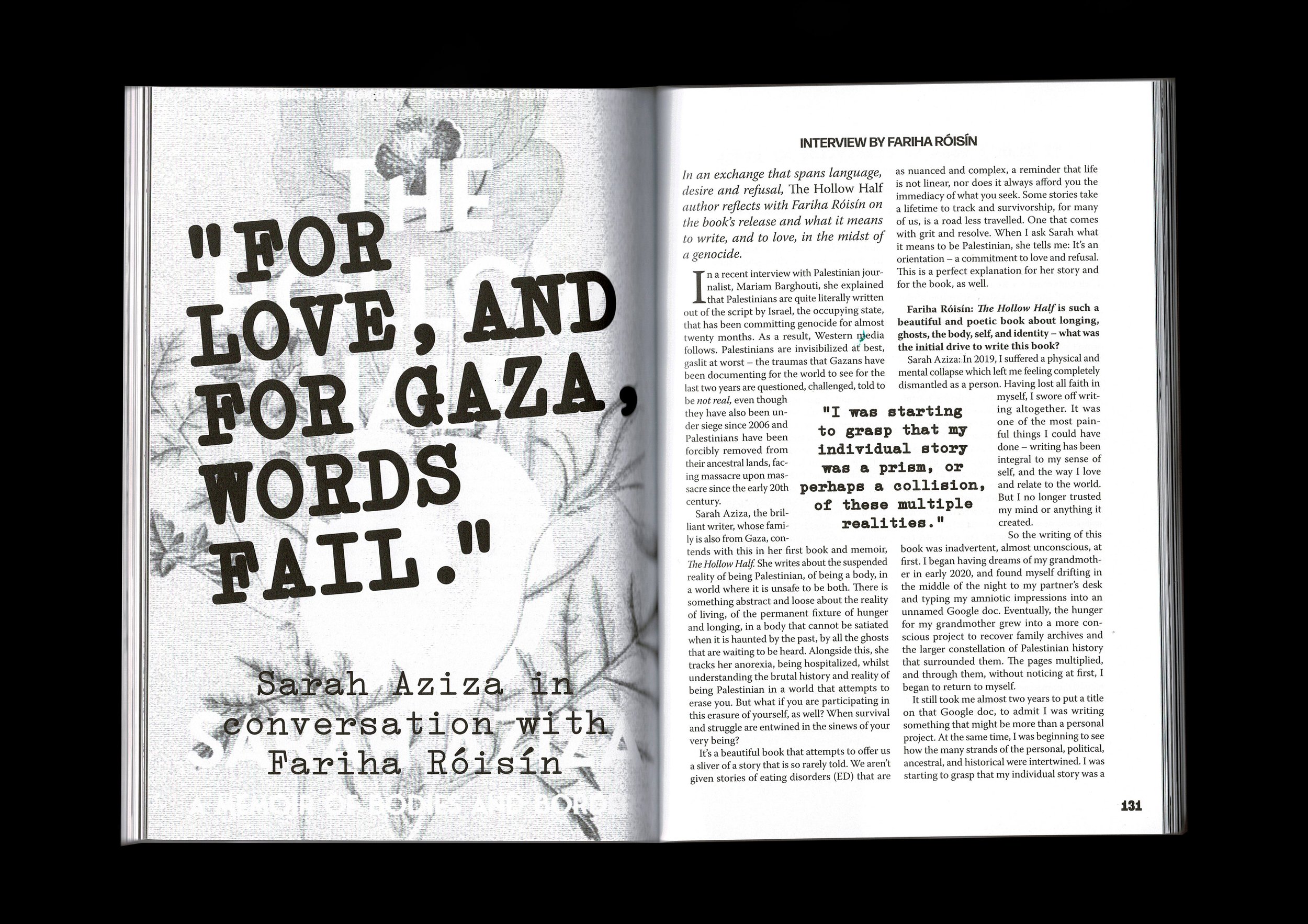

Threadworms, From the Archives: Sarah Aziza in conversation with Fariha Róisín

“For Love, and For Gaza, Words Fail.”

Congratulations are in order for Sarah Aziza, winner of the Memoire Award at the Palestine Book Awards 2025, for her incredible memoir The Hollow Half.

Below, an extract from her conversation with Fariha Róisín about the memoir, featured in Worms 10: The Love Issue.

Fariha Róisín: The Hollow Half is such a beautiful and poetic book about longing, ghosts, the body, self, and identity – what was the initial drive to write this book?

Sarah Aziza: In 2019, I suffered a physical and mental collapse which left me feeling completely dismantled as a person. Having lost all faith in myself, I swore off writing altogether. It was one of the most painful things I could have done – writing has been integral to my sense of self, and the way I love and relate to the world. But I no longer trusted my mind or anything it created.

So the writing of this book was inadvertent, almost unconscious, at first. I began having dreams of my grandmother in early 2020, and found myself drifting in the middle of the night to my partner’s desk and typing my amniotic impressions into an unnamed Google doc. Eventually, the hunger for my grandmother grew into a more conscious project to recover family archives and the larger constellation of Palestinian history that surrounded them. The pages multiplied, and through them, without noticing at first, I began to return to myself.

It still took me almost two years to put a title on that Google doc, to admit I was writing something that might be more than a personal project. At the same time, I was beginning to see how the many strands of the personal, political, ancestral, and historical were intertwined. I was starting to grasp that my individual story was a prism, or perhaps a collision, of these multiple realities. This felt urgent – why had I never been taught to “read” my body, my family, or my life this way? How might the world be different if such connections were made freely, by all of us? Could I find a way to sketch some of this multiplicity in words?

Talk to me about your process. Memoirs aren’t usually so poetic, or so profoundly fragmented, stitching together the story of your life with many different perspectives. How did you land on this way of writing?

It wasn’t easy to find the structure for this book. I tried more conventional forms – linear, chronological, even modular essays, but these all felt anathema to my project. My research and writing was recursive, as was my recovery. I was learning myself and my living as elliptical, full of simultaneous histories and presences, and I felt I had to find some way to approach that on the page. I didn’t want to discipline my prose – “traditional” Western rules of craft mimicked the very forces I was trying to resist politically and personally. For example, the notion of individual characters with legible, linear arcs, or grammar that behaves predictably every time, the demand to “show” and not “tell” while at the same time serving as a tour guide of any non-Anglo-Christian cultural references. These may work when the goal is to represent a reality that hews to the many assumptions and cultural frameworks of the Anglophone, Western reader – but I was rejecting that.

So I experimented. I wrote stories separately, then together. I listened to my body, which held a lot of the answers about which historical and personal and visceral touchstones were important to sync in the text. I had my English bend, inflected it with Arabic, and wove actual Arabic text throughout. I let music into my prose – which is why I think it sounds more like poetry to a lot of readers. And I broke up the narratives with silences, with questions, with ghostly presences, with multiple interpretations – not as gimmick, but because these helped create the truest approximation of how I move through the world. My body is an interruptive, jostling, inconclusive, saturated, and deeply political place.

You write, “Other ghosts withhold their form, moving like breath or sound. I feel the march of them all, building like pressure between my wing bones…” This book felt like it was in conversation with ghosts of your past as well as your ancestors. How did you heed the call of these ghosts, of these ancestors?

I certainly agree that this book is a conversation—I’d use the word “collaboration”—with ghosts and ancestors. But it wasn’t always that way. At first, I was fairly absent from the text. I saw my story as a wreck which was incongruous with the beautiful, heroic lives of those like my grandmother and father. If I investigated that wreckage it was not to redeem it, but only as a vantage from which to view political and historical realities beyond me. But the archive began to get a hold of me. The ghosts were not willing to accept my role as mere spectator or stenographer. They saw me as their kin, and they needed me to engage with them not just mentally but emotionally, spiritually, physically…

Which is a “woo” sort of way to say, I became a subject too, a protagonist in the larger, overlapping, multi-temporal unfolding that is Palestine, that is a family, that is self. My body taught me a lot – it reacted profoundly, both painfully and positively, as my excavation deepened. It insisted on knowing that I was enmeshed in these stories and places, no matter how distant they seemed. In this way, I began to learn to collaborate, to understand the ancestors as present, and my many selves too. It’s a dynamic place of exchange.

I remember you speaking about your father’s relationship to Gaza, the sea – I sense so much longing in your personhood and in that relation to Gaza, or maybe I find that Palestinians are in constant longing, for a place where you are from, but cannot return. Tell me about your relationship to longing.

Longing has been a difficult thing to navigate for me, historically. I didn’t always have language for it. The narrative I was told about myself was that I was “lucky,” much more lucky than most Palestinians, with my U.S. passport and relative safety. Of course, on one level, that is very true. I have privileges. Yet I think denying our longings can be dangerous, both politically and personally. It can be a form of silencing, forcing contentment inside conditions that are actually oppressive. It can suppress resistance and submerge our instincts. So I approach longing in this book with seriousness, as a place of wisdom. It is a place of pain, but it can also be a map toward a world closer to that which we deserve – one in which homelands are returned to, in which queer love is embraced, and bodies are free.

Fariha Róisín is the author of How To Cure A Ghost, Like A Bird, Who Is Wellness For? and most recently, Survival Takes A Wild Imagination. They live and dream between Los Angeles and Hastings, UK.