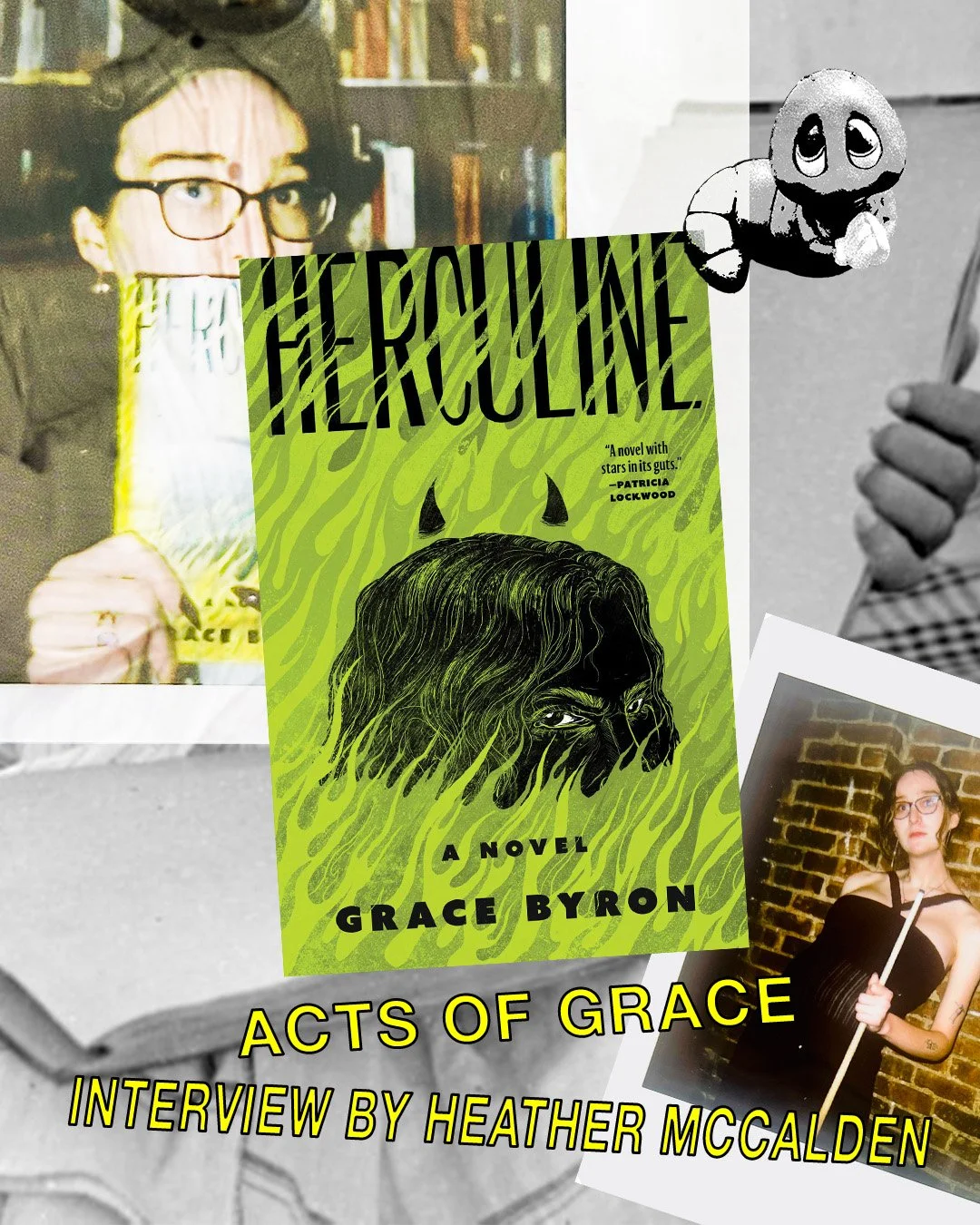

Acts of Grace

Interview by Heather McCalden

Photos by Heather McCalden

It is a fascinating thing when a writer, primarily known for criticism, publishes a novel, particularly one oriented toward genre. The choice to employ certain aesthetics or conventions by someone with heightened awareness of how these codes register in society reflects major insight into the cultural moment. Enter Grace Byron, a critic and essayist, whose debut novel Herculine engages the blood and slime of horror through the ketamine-dusted lens of literary fiction. The story follows an unnamed protagonist as she departs the hellscape of freelancer NYC life to pursue a more harmonious alternative on a trans commune nestled in the Indiana wilderness. Things go awry when it’s revealed the “peace” of the commune is governed by partnerships with demons that allow the characters to live out their dreams in exchange for frequent (and graphic) possession. A tale of desire, compromise, and fear, Herculine reads as a statement about the perils of existing in a time when reality feels thin and ethics exist only in legends. But do not despair! Humour is alive and well, at least from Byron’s perspective. Written in a cadence readers of Lauren Oyler and Marlowe Granados will immediately recognize, Herculine demonstrates how the wry, ironic voice of contemporary heroines effortlessly melds with horror. Chilling, but ultimately hilarious.

Heather McCalden: How do you feel about genre? What is your favorite genre, and did you entertain other genres for Herculine? Was this novel always conceptualized as horror?

Grace Byron: I love genre. I grew up watching Star Trek and X-Files and reading C. S. Lewis. In many ways it was inevitable I would write something more sci-fi or surreal, but I had originally planned to write something more straightforwardly literary. I think there is sometimes a false conception that literary and genre can’t mix—but they always do. Good writing exists across all sectors. Besides, everything is some genre or another. Domestic fiction, the suburban novel… All of these are distinct genres, we just never call them that. Sometimes genre is more about marketing than about craft. Herculine started as a voice more than a plot and the demons slowly crept into the character’s daily life and nightmares. Then they took over.

What do you think horror is actually about?

I think good horror–according to my boyfriend Dana—uses the fantastic to tap into a human emotion or fear and magnify it, shed light on it, and twist the knife in deeper. It exposes a weakness. When demons start appearing in Herculine, they’re telling the narrator she’s a bad person. They interrupt her daily life in New York and start to prey on her insecurities–her fear that she is sinful or evil. She begins to wonder if every little thing she’s told herself about being a “good” person has been a lie–and what it might mean for the cozier side of her life.

“I think there is sometimes a false conception that literary and genre can’t mix—but they always do.”

In Herculine there’s a chapter that references Arthurian mythology. How does this mythology feed into the novel’s consciousness/structure/mood? Why this set of references in particular?

I think King Arthur is similar to Christian mythology, which is the main lore that the book draws on. Arthurian Romances draw on the deadly sins—lust especially. So there was a natural link. I also grew up with an uncle who loved King Arthur and Parzifal and all of it, so it was something I was well-versed in. I took a class on it in college too. When the narrator goes to her grandmother’s house and learns about the joys of living life outside the mainstream Christian world she grew up in–some of that was inspired by my beloved uncle who recently passed away. I think that the narrator sees the world in these mythic binaries but this trip to her grandma’s is the first fracture to that dualistic kind of thinking.

How did you consciously construct Herculine around humor? Is there a scene in the book you are particularly tickled by on account of its humor?

I don’t know if I did this consciously but on some level the book is a comedic monologue, no? The narrator is afraid to stop speaking. She’ll cry. So instead she laughs. I think the first chapter has a lot of my favorite jokes. “God, our heavenly landlord, isn’t the nicest man either.” The narrator’s biggest fear, at first, is rent. The material conditions around her suck yet also provide fodder for her bits. But as time goes on she's struggling to laugh at the sleep paralysis demons, whether twinks, clowns, or something more sinister.

“Herculine started as a voice more than a plot and the demons slowly crept into the character’s daily life and nightmares. Then they took over.”

What was the soundtrack to writing Herculine?

A lot of sad music. The classic yearners across genres: Phoebe Bridgers, Bright Eyes, Johnny Cash, Mitski, Big Thief, Fiona Apple, Ethel Cain, Dolly Parton, Tori Amos, Sufjan Stevens, Patsy Cline. And a lot of techno—I’m a big Kilbourne fan. I mostly listen to instrumental music when I’m doing serious drafting.

In an interview with Cultured Magazine you said, “The New York novel is over,” but I honestly read Herculine as a New York novel. Not only does the city exert a geographical pull through the narrative, but nothing seems more New York to me than making a blasé deal with a demon to get everything you want. I guess I see the New York novel as a mentality rather than a location, but I’m curious how you define a New York novel, and what was the last great one in your opinion.

Oh I think that’s fair. But she leaves New York. Most of the book is about the Midwest and its pull. I suppose the fantasy of leaving New York is also contained in the NYC novel too but I’m not so sure this book is about urban life at its core in the same way it is about spirituality or demons or heartbreak or politics. To me, a New York novel has to be mostly set in NYC and about a young(ish) person tuned into mainstream culture, politics, and precarity. At least in the way many of us are talking about right now. Speedboat by Renata Adler for instance was a big influence on the voice of this narrator. As were certain portions of Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts.

Examples of what I would call a NYC novel include Acts of Service by Lillian Fishman, Information Age by Cora Lewis, Bad Behavior by Mary Gaitskill, Luster by Raven Leilani, Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich, Horse Crazy by Gary Indiana, Jazz by Toni Morrison, many books by Salinger, The Bell Jar by Plath.

They range the gamut. Some are good, some are bad. Some of these are set in New York but may not be “New York novels,” which again goes back to the idea of the marketing gimmick. All of these definitions escape us so quickly. I just think we have enough good ones now. We can try other temporalities and geographies. I think my book just dabbles rather than lives in New York.

How do you take an emotion or a shade of thought and transform it into language? What is your process for distilling ideas and putting them into sentences? How is this different when you’re writing criticism versus writing fiction?

With fiction, I write very intuitively and in long, mostly daily spurts. I try not to think too much beforehand, but to let it be as automatic as possible. It’s alchemy. It’s mysterious to some degree. With nonfiction, I usually read and work backwards from there—it’s more mechanical.

Who are your favorite critics?

So many. Anahid Nerssessian, Tiana Reid, Jamie Hood, Jane Hu, Christian Lorentzen, Andrea Long Chu, Merve Emre, Tyler Foggatt, Jack Hanson, Arielle Gordon, Marissa Larusso, Joanna Biggs, Hannah Gold, Charlotte Shane, Arielle Isack, Kate Wagner. Historically: Jenny Diski, Linda Nochlin, and Gary Indiana. I have absolutely made many omissions and I’m sorry. Despite living in a criticism crisis, we have many shining stars.

In terms of your criticism, is there someone you model yourself after? What is your foundational framework for criticism?

I think the humor, wit, and general interest inherent to Jenny Diski and Patricia Lockwood is where I shoot my arrows. Who knows if I succeed. I don’t want to get fenced in. I’ve been told my writing has a strong political bend, which is probably true. I usually aim for a few moments of sparkle and barbs alongside the textual analysis. I admire writers like Charlotte Shane who can be so political, thoughtful, dedicated, and gentle in their prose. I think I’m a bit spiky, for better or worse. I hate being hemmed in.

What is your process of critically engaging with a text?

Read everything first. Analyze later. My professor Dr. Terri Francis taught me this. I inhale without judgement, then think later. Just see. Draw connections later. I wait to read secondary sources until after the first draft.

“With fiction, I write very intuitively and in long, mostly daily spurts. I try not to think too much beforehand, but to let it be as automatic as possible. It’s alchemy. It’s mysterious to some degree.”

What are some of your favorite essays of all time, alternatively, can you name a text you find to be perfect.

Skating to Antarctica by Jenny Diski is an all-timer. Same with Holy the Firm by Annie Dillard. Nothing out of place, not even a coma. Singular essays: “Three Times” by Charlotte Shane, “Doomsday Diaries,” by Sarah Aziza, Patricia Lockwood on Nabokov, “How do we write about love of cock?” by Adora Svitak.

Is there anything good on television anymore?

It’s grim out there. I’ve been watching RHOSLC more than “real prestige” TV. I do love a British murder mystery, I thought Ludwig was pretty good. I also liked The Residence and Poker Face and of course The Rehearsal’s new season. But I don’t watch as much new TV as I once did. Maybe I’m consuming less trash, maybe my taste has sharpened. I wanted to like Task because I loved Mare of Easttown, but alas I did not.

In your essay “Who is Universal?” you write, “Substack rewards writing about envy, about the personal, regurgitating personal proclivities for clicks, allowing the cattiness out of the bag. The times my writing does the best here are when I go for the jugular or spar for political optimism. When instead I write about a random discovery, I see numbers drop.” I’m haunted by this statement because it indicates that people connect to writing in the same way they connect to reality TV: through disgust. I get the sense that people enjoy reading/consuming this type of content because it recognizes an emotional perversity that typically gets suppressed. Is this an accurate reading of the situation? Is there a way out of this doom loop? Is there a way to make discovery and wonder more appealing than pettiness?

That’s a good point. A lot of criticism is about disgust, but I don’t know if it’s always a doom loop. Some things we should be disgusted by. However, petty disgust is trickier. Things have to warrant a certain level of notice to be worth criticizing. Wonder is difficult. We don’t always want to be taken on a journey, many readers want it quick and dirty, hot and heavy. I get that. But sometimes I want to walk around in a writer’s head—to get lost as they do, to come unmoored and arrive together again in a new place. That can be criticism at its best: a journey. But in a world of clickbait, it’s hard to regain our attention span. Maybe that’s why I love a lot of nature writing. There doesn’t have to be a “thesis.” You can write what you see. I think that’s why I enjoyed writing about horseshoe crabs recently so much—I could discover, gather, not harness or maintain.

What is a novel or essay you dream of writing in your lifetime?

One day I hope to write a long piece on Ursula K Le Guin that gets at why she’s so meaningful and hopeful to me. Same on Jenny Diski. Making what you truly adore interesting is not an easy task. One day I want to tackle Lena Dunham’s oeuvre. I also have a piece on wrestling with Sheila Heti somewhere in me–but not yet.

Grace Byron is a writer from the Midwest based in Queens. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, New York magazine, The Nation, and Vogue, among other outlets. Find her @EmoTrophyWife. Herculine is her debut novel.

Heather McCalden is a multidisciplinary artist working with text, image and movement. She is a graduate of the Royal College of Art and has exhibited at Young Space, 99 Canal Street, Tanz Company Gervasi, Roulette Intermedium, Pierogi Gallery, National Sawdust, Testbed 1, and Seattle Symphony Orchestra. In 2024 her debut memoir The Observable Universe was published concurrently by Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK), Hogarth Books (US), and Editorial Siglo (Argentina, Spain). William Gibson, author of Neuromancer, called it, ‘A gifted writer’s brilliantly innovative approach to autobiographical non-fiction, syncing a narrative of profoundly personal emotion with the invention and evolution of today’s cyberspace.’