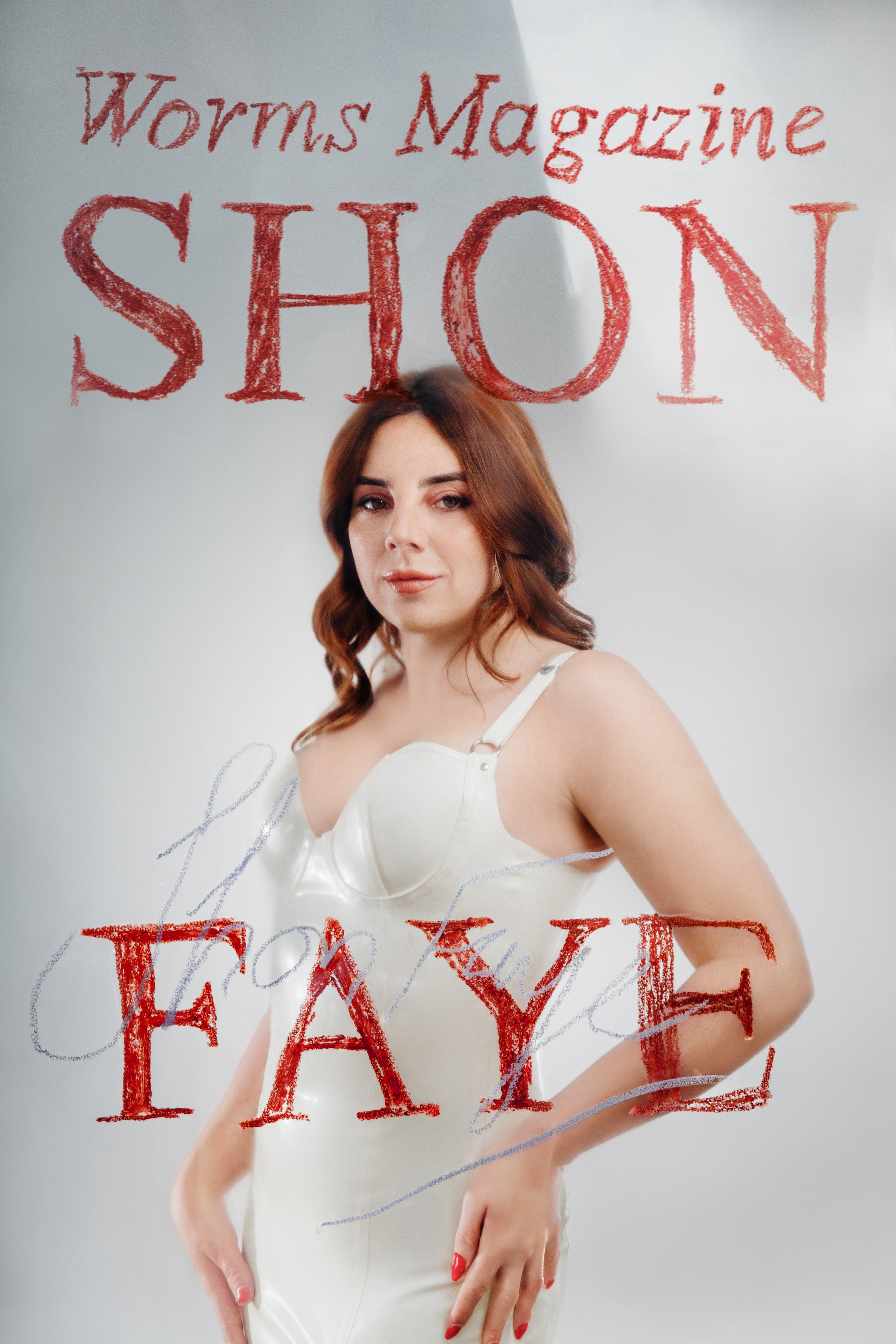

WORMS 10 in Colour: Shon Faye (Copy)

A Heart That Still Beats

In conversation with P. Eldridge, Shon Faye reflects on the aftermath of The Transgender Issue with her latest book Love in Exile, the vulnerabilities of dating while trans, the ethics of memoir, and why love—like exile—is both a burden and a choice.

Interview by P. Eldridge

Cover Shoot:

Shon Faye for The Love Issue

Photography by Minu

Styling by Sabrina Leina

Set Design by Soo Hahn

Art Dept Asst. by Rain Gilani

Makeup by Hannah Gallery

Hair by Luke O’Reilly & Katherine Fuller

Illustration by Rifke Sadleir

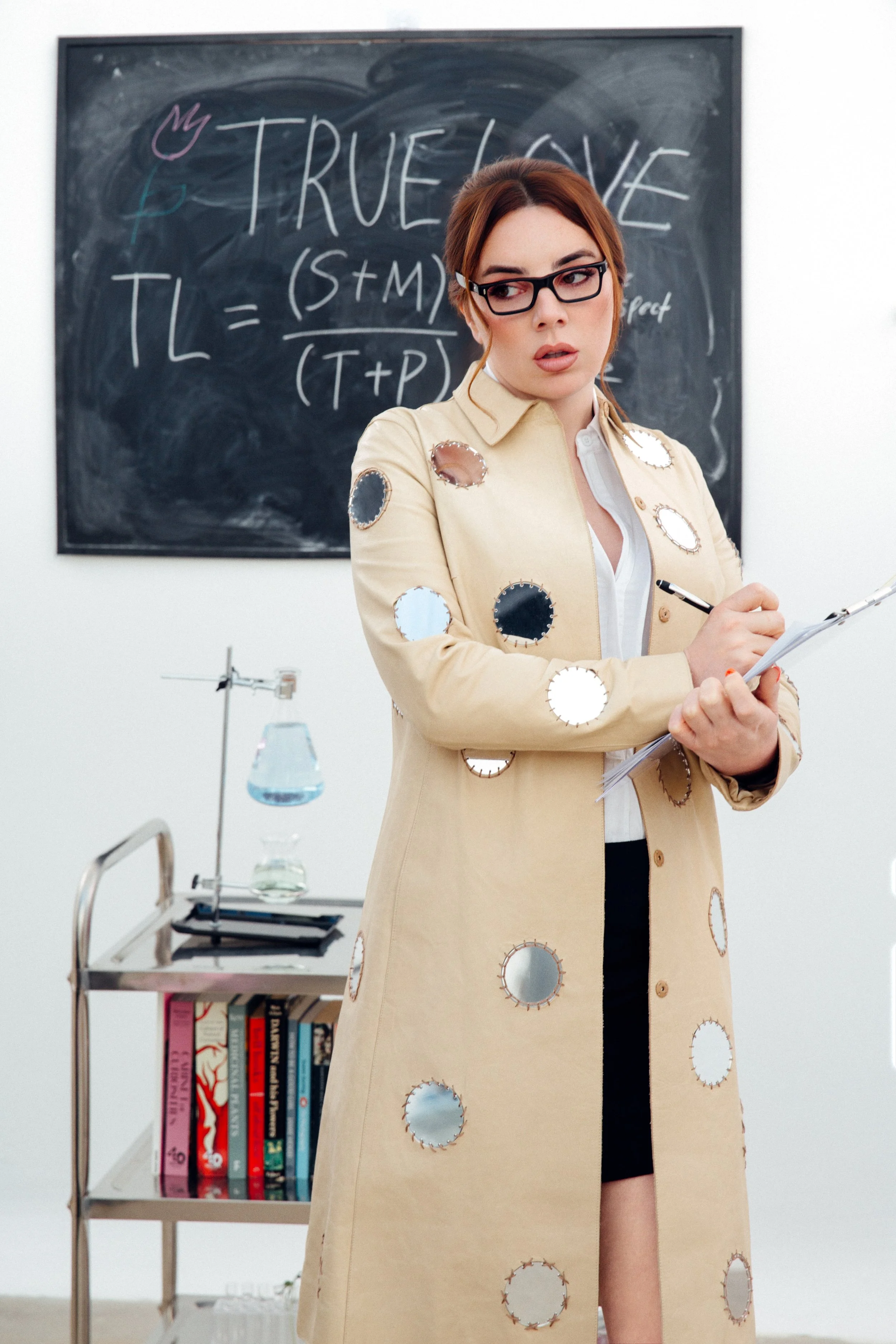

It’s the morning of the Supreme Court handing down yet another ruling against trans rights, and Shon Faye is radiant under studio lights. We're in East London, surrounded by rail tracks and makeup brushes, in the kind of liminal glamour that often defines the public lives of trans women. As the cover shoot wraps, we find a moment to sit together the day following. The mood is both charged and tender; laughter offsetting fatigue, grief braided with insight. Faye, best known for her landmark book The Transgender Issue, is no stranger to navigating public discourse with incisive clarity. But Love in Exile, her latest work, is something else entirely. A memoir stitched from heartbreak, addiction, and spiritual reckoning, it marks a turn inward and, paradoxically, a deeper reach outward. What unfolds between us is a conversation both vast and intimate: about the failure of heteronormative scripts, the politics of romantic visibility, the mess of emotional truth, and the strange, aching joy of choosing to stay; in one’s body, in community, in love. At the heart of it is a question that defies neat endings: What happens when we refuse to be explained, and instead insist on being felt?

The following is an extract from the full feature interview in Worms 10: The Love Issue. If you would like to read the full interview, consider becoming a member at the link below or purchasing your very own copy.

P. Eldridge: Shall we start with yesterday’s ruling? It felt strangely cosmic that we were doing your cover shoot at the same time the Supreme Court handed down its decision against us.

Shon Faye: Classic. When I was a journalist, they’d always choose that day—the day a trans person’s rights were being stripped—to interview me.

[Laughter] But, I mean… as a fellow tranny, I am allowed to ask these questions.

[Laughter] You are. You’re absolutely allowed.

How are you feeling?

I feel devastated. While we were shooting yesterday, I posted very briefly on Instagram to mark the moment, and immediately remembered why I’d taken lent off the platform. I was in a kind of bubble.

Today I finally read some of the Guardian’s coverage. By summer, we’re going to have official guidance saying we can’t use public toilets. I had a panic attack. It hit me, Oh, right, it really is that bad. This morning I told myself I felt fine. That it couldn’t possibly be real. But I’ve realised that’s dissociation, a trauma response.

For several years, I honestly believed transphobia wasn’t the main issue in my life. I was more focused on addiction, family abandonment, and trauma. I was in therapy for a lot of things. When therapists tried to talk to me about transphobia, I’d often shut it down. I thought of it as too basic, too obvious. But I’ve come full circle. When transphobia becomes this publicly sanctioned—this aggressively visible—it re-traumatises you. I don’t have a neat answer for how to manage that. But like anything, the first step is naming it. Recognising what’s happening so you can begin to accept it and adapt as best you can.

That kind of adaptation—the constant morphing—can feel brutal; it's exhausting. I relate. My therapist is a trans man, and he often encourages me to begin from the standpoint that being trans is simply a part of who I am – not the entirety. It should be an attribute I can inhabit comfortably, a marker of identity rather than a defining narrative. I do understand that, I really feel it. But when the Supreme Court legitimises transphobic rhetoric through legislation, I can’t pretend that being trans is just a starting point. It becomes the beginning, the middle, and the end. It seeps into everything. I wish I could compartmentalise it—say, I have blue eyes, I was born in Australia, I’m a writer—and have that be enough. But I can’t shed it that easily. I'm a trans human, and that’s the identity I meet the world with, whether I want to or not.

That’s because the world forces you to, isn’t it? When you lived in Australia, your Australianness wasn’t at the forefront. But here, you’re made constantly aware of being foreign.

In my everyday life, I don’t feel that being trans is central to who I am. I suppose that’s what I cling to. What’s also difficult, though, is the way the cultural tide has shifted. That’s why I have so much admiration for trans people who remain committed to trans communities. I’m thinking of people like Torrey Peters, Travis Alabanza, Tom Rasmussen, Morgan M. Page – my friends, people whose work is wholly rooted in the trans experience.

In contrast, I think my work has always been a kind of conversation with cis people, not exclusively for or about trans lives. That’s a deliberate choice – for better or worse. Yet, I deeply admire those who do centre their work around transness, because the more you assimilate into the cis world, the more your transness is seen as a problem.

The less I speak about it, the less I think about it. Sometimes in my private life, it barely registers – or maybe I’m actively trying to outrun it. That comes up in my romantic life too, which ties a bit into Love in Exile. I often feel relieved when I’m dating a cis man and he says, “I don’t really know much about trans issues.” Part of me is thankful – that’s my burden, my trauma, my work. I’m glad he doesn’t know. But it’s also maddening, because what he’s really saying is, “You’ll have to teach me everything.” And that, inevitably, makes me resentful.

We were talking about this yesterday – how, in these situations, you end up becoming the teacher, the therapist, the mother…

Exactly. Even though I love them dearly, I do think about this with my cis women friends. Having those relationships has been incredibly healing, especially with cis women who never knew me before I transitioned. There’s never been a moment of adjustment; they’ve only ever known me as I am. But sometimes I get so comfortable in those friendships that I almost forget; until something like yesterday’s ruling happens. Then it’s like, Oh right. They really do see me only as a woman, which is sweet, in a way, but also jarring. Because I have to remind them: this is different for me. Even though some of them are thinking about this ruling—the Supreme Court, the rise in TERF rhetoric—as much as I am, they’re still not experiencing it the same way.

“Love in exile” is such a resonant phrase. It evokes longing, resistance, and tenderness held at a distance. Could you speak to what exile means to you in the context of love? Does it describe a condition, a choice, or something inevitable?

Exile, if you think about it historically, is a kind of banishment; sometimes self-imposed, sometimes forced. Across human history, exile is usually politically motivated: a removal from a community, a denial of belonging. That’s why I was drawn to it, it’s not a natural state. It’s something done to you. It carries a wound, a kind of severance.

I was interested in the idea that love is something we all deserve, and yet some of us experience a kind of banishment from it; from accessing it in its full, social, recognised form. The title, for me, originated from that sense of exile. I’m not the only one who’s used the metaphor. Jamie Hood has used it, and I’m sure other trans women writers have too, so I don’t claim it as entirely original. But for me, it captured something very specific I was thinking about: the experience of loving and being loved by—mostly—straight cis men. That’s where my romantic life has tended to unfold. In that space, love and heteronormativity are deeply entangled. I was essentially positioned in the role of a straight woman, and yet I was exiled from it; from that normative romantic script. Trans women, by and large, aren’t granted the role of wife, girlfriend, mother. That archetypal place in domesticity and love, it’s not made available to us.

There was a point when I thought I’d found a way around that. I thought I’d gamed the system, in a way. I had a partner who wanted children. It’s a perfectly natural thing to want, and when we spoke about it, it felt like, had I been open to it, he would’ve wanted that future with me. But even in that possibility, I was reminded, Here’s something I can’t do.

For me, exile speaks directly to transness. That’s the point of departure, the experience of being shut out of what you’re told is ordinary, universal, natural.

Do you think exile is something you’ve come to accept, or are you still trying to find your way out of it?

I’m definitely still trying to work my way out. Some of the criticism of the book has been along the lines of, Why don’t you just queer your desires more?

Sapphic.

Exactly, like, why am I not leaning more into that? Honestly, the simple answer is: it just doesn’t happen for me. My options have always been cis men, gay men, and of course, trans men too. On this book tour, a lot of trans interviewers have asked, What about T4T? Sometimes, weirdly, it feels a bit accusatory, as if I’m being interrogated about my sexuality.

[Laughter] I don’t have any of that for you.

[Laughter] Thank you. I suppose the assumption is that if I dated more queerly, or if I dated a trans man, I’d automatically have this blissful, non-heteronormative relationship, free from all the issues I’ve written about. But that just isn’t true. I often think, Have you met straight trans men? Because some of them—like cis men—would prefer to date cis women. It feels more affirming for them, and fair enough. Heteronormativity doesn’t disappear in queer relationships. It still shows up, because it’s structural, it’s not just about the individual’s gender history. The fact is, I’m attracted to men. Yes, I could be with a man who’s also trans, but I’m still dealing with the same dynamic. Unless I go fully celibate—which I’ve tried, I’ve had my celibate phase—I’m always going to be in some sort of relationship with heteronormativity.

And masculinity.

Yes, exactly. Loving men means constantly contending with the expectations placed on femininity – that whole framework is just there, waiting. It’s not something I can opt out of. If I could change my desires, I would have by now. With Love in Exile, the idea was also rich metaphorically, not just in terms of love, but in other areas of life. I became interested in women who aren’t mothers, for example women who don’t occupy that central, culturally affirmed role. I hope readers can see that the book uses exile as a broader metaphor too. Even when I write about addiction, there’s that same sense of exile: of being pushed to the margins, treated as an outcast.

You've spoken about exile in terms of love and identity – but are there other frameworks, spiritual or otherwise, that have shaped how you understand that sense of separation or longing?

I suppose in terms of love, there’s the addict element. But also, oddly, Catholicism. So much traditional Catholic prayer talks about exile; about this life being an exile from the face of God. The belief is that when we die, our exile ends, and we’re reunited with God. That to be mortal—to walk this earth—is to be estranged from your true destiny, which is communion with the divine.

I’m not a practising Catholic, but I grew up with that language. That idea really stayed with me, that we’re in a kind of spiritual exile until death. The book, in a way, ends on that tone: that the ultimate resolution to the feeling of being unlovable doesn’t come from people, or love, or achievement: it comes from a relationship with God.

Yes, exactly. Not from self-help, or even therapy. In the final chapter ‘Agape’, you pray.

I think the girls who get it will get it. There was a review in the U.S.—a good review, really—but it said that the final chapter on religion felt awkwardly extraneous, though my prose was conversational enough that you “wouldn’t notice.” I thought, that’s so interesting, that someone could read that chapter and see it as out of place. Even a good friend of mine, who read the manuscript early, said, “I don’t really get the last chapter. It doesn’t quite fit.”And the truth is, I can’t fully explain why it makes sense, it just does. You either feel it, or you don’t.

It was my favourite chapter. Don’t get me wrong, the first broke my heart—I was sobbing—but ‘Agape’ really stayed with me. It felt like a reckoning, and also a kind of welcoming – an acceptance of exile as a state of being that you’ve chosen to live in.

Well then, you’re one of the girls who gets it! [Laughter] That’s exactly the intention. The core message of that chapter is: only spirituality can heal that deep sense of lovelessness – the part that surgery, hormones…

…men…

…cannot fix. Exactly, men don’t fix it. Even the good ones. Even your best friends can tell you they love you, and you can still feel utterly revolting. Even therapy. I’ve done loads of it, I believe in it. I’m probably going to train as a therapist at some point. But that core wound—that deep belief about your own worth—I’ve found that only spiritual practice, what I call ‘Agape’ in the book, actually touches that place.

In a world that so often demands resilience from trans people, did you ever worry that your vulnerability might be misunderstood – either by readers or even by yourself?

Maybe, but honestly, only really when it came to writing about sex. That was the part I was most afraid of. I used to talk very openly about sex online. I was a bit of a social media girl, especially on Twitter, and Tumblr too. I’d speak about sex the way I would with close friends: candidly, sometimes irreverently. But as my profile grew, I started to realise how exposing that could be, especially in the UK. As a trans woman, you can’t talk publicly about sex without being weaponised. I found some of the smears and demonisation I received early in my career really traumatising. It made me retreat. So coming back to write about sex, and to do so honestly, felt like a big risk. Even then, I could’ve been far more graphic. If I’d been writing purely for trans readers, I would’ve said more. But sometimes, the power of writing about sex is in what you don’t say, in what’s held back.

Do you think refraining is a cultural hangup? I’ve got a lot of trans girls in my life, and we do talk about sex a lot.

Yeah, I think it is cultural – very British, in fact. There’s a kind of restraint around talking about sex, particularly as trans women. I always say that when you meet other trans girls—especially if they’re straight—you end up talking about surgery and men. Those are the two things we’re allowed to be intense about. But that’s because they’re about the body.

In a society where you’re constantly masking—trying to make your transness less visible or more palatable for others—your body becomes this battleground. You hide it physically, you hide it in how you speak, how you behave, how you socialise. Because people are deeply uncomfortable with transness. So you end up sanitising. I’ve definitely sanitised parts of my sex life. Part of that’s just because my sex life is boring now. [Laughter] But when it wasn’t, I wasn’t going around to my cis girlfriends and saying things like: “I slept with this guy who calls trans girls ‘traps’ and loves trans porn.” Because they’d be horrified—rightly so—and tell me, “You deserve better.” I’d think, I know I do. But at the time, I didn’t believe better was possible.

I remember this one guy who told me that when he and his best friend were sixteen, they both found trans porn on each other’s phones. He said, so casually, “Yeah, we’ve fucked trans girls together before. We’ve had threesomes and stuff.” I still had sex with him. That’s not a unique story. If I’d told that to the wrong people—to the wrong cis friends—I’d have just ended up feeling more ashamed. The thing is, the shame was already there. I didn’t need someone to tell me I should have higher standards. I already knew that. I just didn’t believe I could have them.

I mean, you say that in the first chapter too. When your friends ask how things are going with B., you shut it down straight away: “He wants kids.” There’s this very definitive, we’re not talking about this. You lay out the reality and move the fuck on.

Yes! That kind of reckoning doesn’t end. It’s not like writing about it resolved it, it’s a constant thing in my dating life.

Writing about sex was particularly vulnerable. But—and I don’t think this is arrogant, just an honest confidence in my writing—I’m proudest of Love in Exile because I was really rigorous with myself about emotional truth. I went back and rewrote anything that felt like it was trying to protect my ego. I didn’t want to be performative or evasive. That doesn’t mean I disclosed everything. In the chapter about alcoholism, for example, I don’t list the worst things I did, or the worst things that happened to me. I allude to them, they’re implied. But what I tried to offer wasn’t a catalogue of trauma, it was the emotional truth of addiction.

"Heteronormativity doesn’t disappear in queer relationships. It still shows up, because it’s structural, it’s not just about the individual’s gender history.”

You’ve mentioned before that writing Love in Exile felt like a kind of corrective – a way of responding to the expectations that followed The Transgender Issue, as if the world wanted to see you as fixed or even saintly. How did this book help you subvert that idea of completeness? And, related to that, how did it shift your relationship to success or recognition?

After The Transgender Issue came out, I suppose I felt—especially in the first year or two—that I’d done a good job with it. It’s funny though, because things have gotten so much worse for trans people since its publication. Now, sometimes I catch myself thinking, Should I go back and rewrite parts of it? I don’t know. Maybe. Maybe not.

At the time, there really weren’t many examples of trans women writing political books that weren’t memoirs. The book did really well. For a while, I felt—or at least, I perceived—that I’d become some sort of intellectual figurehead for trans people in the UK: someone combining media fluency with a kind of academic or political rigour.

When I moved to the UK, The Transgender Issue was everywhere. I saw it on the shelves of all my friends’ flats. You were the trans correspondent we could trust – someone who was both informed and unafraid.

Yeah, I think that became part of my public identity. I remember the moment I realised just how serious it had become – it was when I got the email confirming that Judith Butler had sent through a quote for the book. I just thought, Fuck.

The voice of a generation.

I was in shock. I didn’t think someone like Judith Butler would even read the book, let alone endorse it. That was the moment I realised things were going to get overwhelming. Honestly, I think there's something specific—and quite fraught—about how the liberal left in the UK deals with visibility. There’s this cultural tendency to elevate someone to “talking head” status, to look for a figurehead. I realised pretty quickly that I was a palatable trans person. That, combined with the book, made people more inclined to let me tell them what to think. But that “saintly” projection—being put on a pedestal—made me deeply uneasy.

At the time, I wasn’t long sober. I definitely didn’t feel like someone with a saintly history. I’d been a fucking mess in my twenties. Take something like the HARDtalk interview I did for the BBC. It’s this intense, unedited 25-minute programme that’s had everyone from Hugo Chávez to global heads of state. It’s broadcast around the world on the BBC World Service to tens of millions of viewers. Steven Sackur introduced me by saying something like: “She turned to drugs and alcohol to numb the pain in her life, but then she found her voice… and here she is.” I was struck by how my addiction and recovery had been folded into this redemptive narrative. Because I’d been open—from the moment The Transgender Issue came out—about the fact that I had a history of drug and alcohol addiction. I wanted to be honest about that, I didn’t want to be sanitised. But I could feel the contradictions. On the one hand, I hadn’t lived a neat or “clean” trans life. It had been chaotic. Yet I was now being positioned as a cultural authority, someone people looked to. I’d done the work, I’d started recovery, but I was still deeply dysfunctional in other areas, especially romantically. Still, in nearly every interview, people wanted a happy ending.

I get it, we’re a marginalised group. Even though I might sit at the more privileged end of that, I still came from a history of addiction. Just like so many trans women, you’ll often find some mix of drugs, sex work, or contact with the criminal justice system. That’s what happens to marginalised people when support is non-existent. But the story people want is: “I was a suicidal mess. Then I transitioned. Now everything’s fine.” And the truth is: I’ve always been a suicidal mess. Even after I transitioned.

There’s this pressure to be happy post-transition. It’s so deeply embedded – part of how medical gatekeeping has worked, and part of what the public wanted, at least for a time: a story of redemption. A trans person who overcame adversity and is now thriving. That’s the image that’s palatable. But it’s not the whole truth.

You’ve spoken before about your admiration for Annie Lord’s refusal to romanticise herself in heartbreak. In your own work, were there moments where you worried about appearing too messy or too much? And if so, how did you write through that?

Honestly, by the time I actually sat down to write the book, no, I didn’t worry about that. I had before, certainly. But when I started Love in Exile, I told myself: it has to be messy.

I thought about the writing I’m drawn to—what I love reading—and it’s always the mess. I love reading about women who are unhinged in all the best ways. I’ve said this before, but Detransition, Baby was such a turning point for me. I hadn’t read that much trans fiction before it came out—not as much as I should have, to be honest—and I certainly hadn’t read writers like Jackie Ess until afterwards. But reading Detransition, Baby made me realise: you don’t have to write Pose characters. You can write someone like Reese; someone with misogynistic sexual fantasies that are somehow affirming but also deeply fucked up. Of course, there are things you can do in fiction that you can’t do in memoir, there’s more licence. But I think the reason stories like that resonate is because emotional truth is messy. I’ve always been captivated by that.

There’s something deeply ethical in the way you chose to write with restraint – especially when it came to others, like the person you call B. in the first chapter. Did that kind of self-censorship feel like a wound, or a form of integrity? How do you know when to write through a wound, and when to let it scar in silence?

It felt like integrity. The truth is, I really loved that person, even though they’re no longer in my life. I think I was restrained because, ultimately, I still wouldn’t want to hurt him. There were years when I was furious with him. But even so, I didn’t want him—especially at a moment when he’s living a completely different life—to open the Guardian and see an old story about himself splashed across an extract and think, Fuck.

Yes, I could’ve written more. I had every right to tell the truth, I still believe that. I do allude to how unpleasant some of his friends were. But I wouldn’t want someone to write a book about my worst moments either. I say very clearly in Love in Exile that I have a history of addiction, and that comes with lying, stealing, all sorts of things. But would I want those things written about in someone else’s book? No. So that restraint didn’t feel like suppression, it felt like a commitment to writing with care.

It also challenged me, creatively. Wanting to maintain that integrity pushed me to be more thoughtful, more precise. That boundary helped clarify something for me: What is this book really about? Is it a novelistic memoir that needs to present a two-sided relationship in full, where he becomes a complex, realised character and therefore I either need to fictionalise it or seek his permission? Or is this my story? As much as I confess that I carried all these feelings for him… he’s also just some guy. But the reality is…

…he functions as an archetype, a blank canvas you can paint with broad brushstrokes.

Exactly. That’s the whole point, isn’t it? The person who ruins your life is always just some fucking guy. Because, in truth, he became a subject for my own projections.

I want to begin this next question by reading from Jamie Hood’s How To Be A Good Girl. She writes, “I have convinced myself each relationship failure is a failure on the level of my personhood. Not what did we do, but why am I unlovable? That is, why am I, I.” That really comes through in Love in Exile – this idea that, for trans women, love can feel not like the breakdown of a relationship, but a complete collapse of self. Not that this didn’t work, but there’s something wrong with me

That definitely resonates. I think, in many ways, it captures the last few years of me thinking that way. I’ve moved on from it now, or at least, I’ve moved through it.

“Only spirituality can heal that deep sense of lovelessnes”

Because the book took three years to write?

Yeah. I wonder if Jamie still feels the same way, but that feeling never fully disappears. It’s always there – that question, that lurking sense of being unlovable. But I’ve got better at noticing when I’m spiraling back into it. I wrote about it in ‘The Brokenheart’ chapter. I think, for trans women—though I won’t speak for all of us—there’s a particular cocktail of things happening. I saw a meme recently that said, “You’re not unlovable. You just like boys.” Unfortunately, I think that lands. For me, the thing I’ve had to disentangle is that men—most of them—are just really fucking disappointing. A small minority are outright dangerous, yes, but most are just... underwhelming. That’s why I love Nicola Dinan’s new novel, Disappoint Me. It’s not even complicated, it’s just inevitable.

The capacity of men to disappoint – I mean, that’s not unique to trans women. That’s a universal experience. Norman Fucking Rockwell, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Destiny’s Child, we’re raised on that music. It's part of the feminine condition. But for trans women, I think it becomes entangled with a deeper insecurity; this codependency loop. We’re not the only ones who fall into it, but I think we’re especially vulnerable to it. We end up tying our sense of worth to whether a man thinks we’re lovable, or viable. We assign our whole value to how we're seen by someone we barely know.

On a felt level, though, it’s different. How did you get there?

At the very end of writing Love in Exile, I went through another heartbreak. It wasn’t a relationship, technically—not in the conventional sense—but it was painful all the same. There was a man in my life, and while we weren’t romantically involved, there was clearly something between us. There was energy, a closeness. We were both talking about each other to other people, and eventually, I built up the strength to be honest about my feelings. Then he told me—quite casually—that he was dating someone else. He’d already moved on. I was crushed. It shouldn’t have been the biggest heartbreak of my life. It wasn’t even a relationship, not really. But it was unrequited. Because I’d taken the initiative—for the first time—it felt so exposing. The grief that followed was far larger than the situation justified, and I was lucky to have enough insight to recognise: This isn’t about him. This is old pain.

It’s displaced pain, surfacing.

Exactly. That’s when I realised. I think being in recovery really helped, because in recovery communities, especially around addiction, you notice certain patterns. Most people who’ve struggled with substance use also have issues with love… and money. Always love and money. I knew women in those spaces who had done serious work on love, so I took it seriously too. I hit a point where I felt like I was dying. What made it harder was that I no longer had alcohol or drugs to numb anything. There was no buffer. Like in Melissa Febos’ The Dry Season, I did a year of complete abstinence. No sex. No flirtation. Nothing. I cut all of it out. It was only when I stopped that I realised how much I'd been performing. I thought I wasn’t audacious, but actually, I was. I’d deleted every dating app. I didn’t even have WhatsApp conversations lingering in the background. During that time, I did serious therapeutic work. I started to recognise the roots of it all; the way I’d used men for validation, as a barometer for desirability, for self-worth.

This is all fairly recent, right? Where are you now, with dating?

Yes, this was all while I was finishing the book. When I decided I was ready to date again, I made a commitment: to truly detach. Not the faux-detachment of saying, “I’m taking a break” while still chatting to someone on WhatsApp, still sleeping with a situationship from Feeld, still flirting with the guy at Pizza Union. I mean, actually detaching. Because here’s the thing – for many trans women, especially those of us who transition as adults, femininity often gets constructed at the same time that male attention becomes the go-to form of affirmation. And for me, I’d never really moved past that. That year shifted everything. Even the way I dressed changed, subtly, because I wasn’t constantly trying to get those little dopamine hits of being looked at, validated. At first, it was really hard. But when I came back to dating, what had changed was this: I didn’t need it to affirm my worth anymore. I still went on Feeld, but not for casual sex, I was looking for real connection. What I noticed was that I no longer got the same rush when a man called me beautiful. It didn’t land in the same way. It didn’t define anything anymore.

Was it because you’d already felt it all? Or had you finally developed a sense of self that felt unshakable?

It’s that new kind of neutrality, where even if it is true, even if someone does find me attractive, my inner response is: Okay… but you still want to fuck me.

[Laughter] Boo. Move on. Say something interesting.

[Laughter] Yes! Exactly!

BECOME A FULL TIME WORM MEMBER…

As a FERTILISER, you get a deeper dive into the verdant soils of Worms with extended reads on special features. You’ll get access to all of our content including exclusive newsletters, interviews, podcasts, weekly book reviews and links to articles, as well as an invitation to our monthly bookclub.

The Soil Supporter Membership gives you the complete Worms experience, including the benefits of a FERTILISER + more. Every new magazine we release in the year is yours, plus all the goodies of what we publish online here for you to delve into. Includes Postage.

The Soil Supporter Membership gives you the complete Worms experience, including the benefits of a FERTILISER + more. Every new magazine we release in the year is yours, plus all the goodies of what we publish online here for you to delve into.

The Microbial Membership gives you the complete Worms experience, including the benefits of a FERTILISER + more. Every new publication we release in the year is yours (including the magazine and publishing releases), plus all the goodies of what we publish online here for you to delve into.

The Microbial Membership gives you the complete Worms experience, including the benefits of a FERTILISER + more. Every new publication we release in the year is yours (including the magazine and publishing releases), plus all the goodies of what we publish online here for you to delve into.

The Microbial Membership gives you the complete Worms experience, including the benefits of a FERTILISER + more. Every new publication we release in the year is yours (including the magazine and publishing releases), plus all the goodies of what we publish online here for you to delve into.