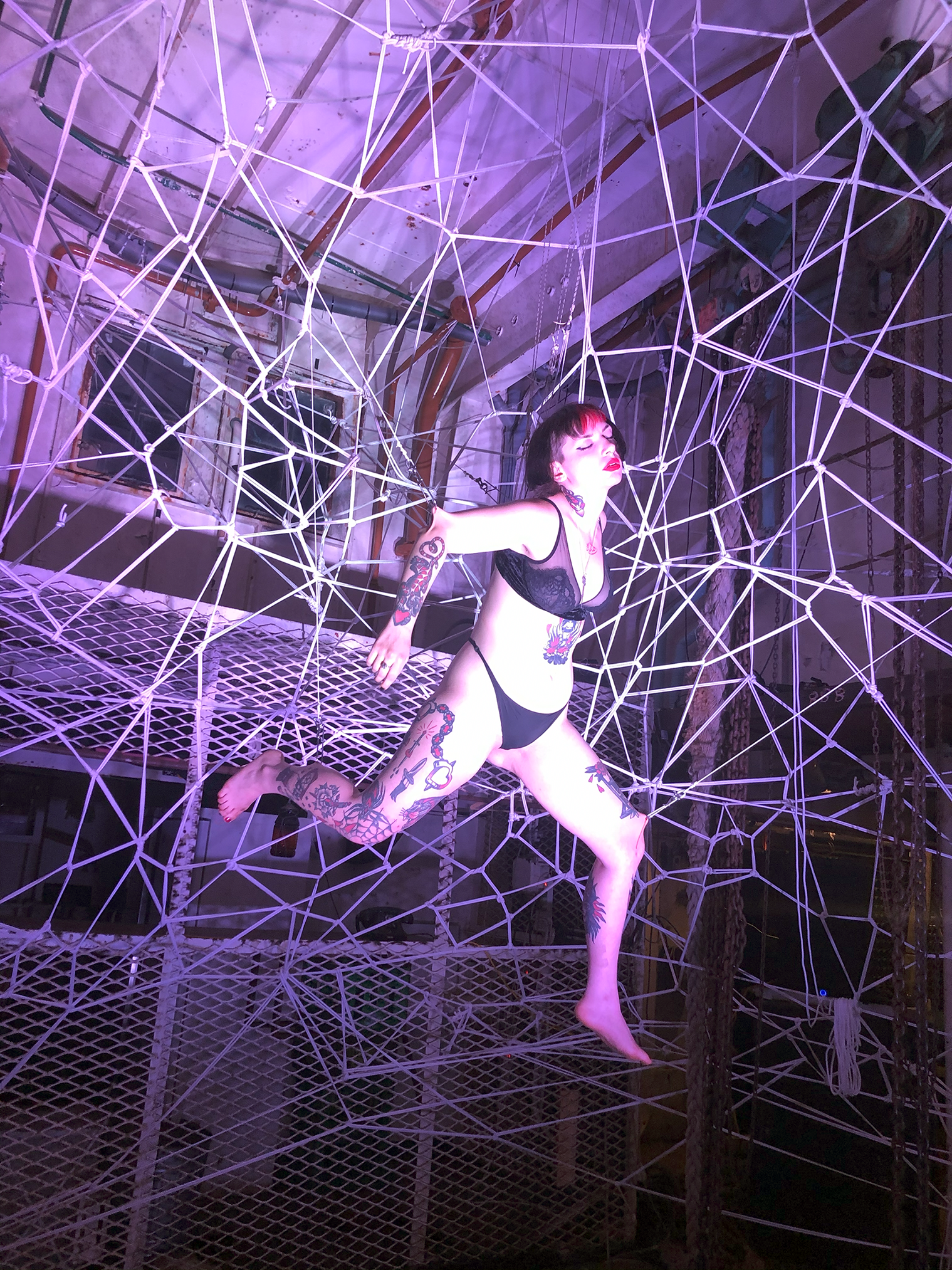

Suspended and Surrendered with Cherry Velour

In March of 2025 I went to see Hana Noelle, who performs under the name Cherry Velour, perform at Ugly Duck Gallery in London. Until then, my approximation to pain performance or BDSM could be narrowed to two very specific encounters: a brutal showing of Angelica Liddel’s Terebrante in El Esocorial, a stones throw from Madrid (which resulted in my dad heckling her as she took a bow but that’s a different story), and a reading of Philippa Snow’s 2024 hit book Which as You Know Means Violence. What I saw that night was a transformative experience: pain, suspension and presence, welded together in a beautiful display of bodily performance and stunning stage design.

Cherry was suspended for the greater part of two hours by a series of hooks piercing her skin. Like a spider suspended in a metallic web, her body still and contorted, made elastic at the entry-point where the blades pierced her skin. Pain demands presence. Pain begs you to pay attention to it. Pain is as physical as it is mental. It’s a sign. It’s your body communicating with you. But what happens when we just let it sit? When we recognise it, acknowledge it, and in doing so, manage to transcend its first petulant layer of demand? What other physical sensations does pain then offer the body? These are the questions that Cherry addresses with her performance. Beyond the tickling, the nipping, the pinching, the cutting, pain can open a well of release to those who seek it.

I was taken by what I saw. The tenderness of the display. The skin-prickling effect of it. The tension between those two, the fragility and the brutality, called to me from a deep place. A couple of months later, I sat down with her and asked her about her world, language and ideas on the questions that seeing her perform had Brough to the surface. I wanted to know about how BDSM frameworks could be applied to other contexts, the transcendence of that practice. Cherry was approachable, loquacious and elegant in her speech. I picked up a copy of Leash once we finished talking. I was glad we shared a common interest in Dennis Cooper.

Fantasy, world-building and narrative, when used effectively, are some of the most powerful tools an artist has at their disposal. It is what makes art go from the personal to the universal. Cherry Velour wields that tool with an unmistakeable effect. Taking herself to the limits of the physical experience, she generously invites her audience to reflect on the nature of surrender, play and pain beside her.

Arcadia Molinas: Hi Hana. Tell me a bit about your practice as an artist.

Cherry Velour: I’d say my practice is rooted in transformation, using BDSM as a framework for exploring themes of identity, surrender, and autonomy, often using pain practices and discomfort as a vessel for that transformation. My work is really relational and as such, I prioritise collaborative work. I’m really interested in what happens when people are invited to sit with discomfort together — how that can transform both the performer and the audience.

What are some of the books that have influenced you the most?

Leash by Jane DeLynn is a huge one. First off, it’s one of the few kinky novels out there written by a dyke, so that perspective is obviously important to me. It’s about transformation, power, surrender, shame, and the collapse of the self. It depicts a brutal, toxic, fucked up BDSM dynamic that I would never condone in real life, but that’s why I’m drawn to it — it’s fantasy, and I think in fantasy we should be able to play out our darkest thoughts, our most depraved imaginings, and see where it takes us. And the book makes you ask — what makes this wrong? Where is the line? What would make it right? It pushed even my boundaries as a reader. And as a performer, those are themes and questions I’m really interested in. I’m a huge fan.

The Sluts by Dennis Cooper is brutal, disorienting, obsessive. Everyone is performing for someone else. It’s pieced together through chat logs and — there’s no truth, no narrator, just fragments of reality blurred with fantasy. My work straddles that threshold, too: performance exists between what’s real and what’s constructed, and pain performance especially.

Finally, Bob Flanagan’s poetry is incredibly important to me, especially in the context of his life and performance work. As a lifelong sufferer of cystic fibrosis, he was always in pain. But instead of being passive in that, he chose pain through BDSM and performance. He used suffering as a way to survive on his own terms, to reclaim agency, and to turn the unbearable into something meaningful. That’s at the core of my own work too: pain not as metaphor, but as method. His writing is blunt, raw, humiliating, sometimes funny, and always deeply sincere. He leans into the discomfort, the grotesque, the ugly. Nothing is polished or sanitised. And I carry that with me a lot - I don’t want to be pretentious or overly conceptual. I want my work to be grounded, embodied, and emotionally real. His poem Why?, where he lists dozens of reasons for enduring pain—some tender, some messed up, some mundane—gets referenced a lot for good reason. People ask masochists “why” all the time. There are infinite reasons. And maybe none of them really matter.

Where Cooper and DeLynn explore obsessive fantasy, Flanagan brings you the reality — bleeding, sick, laughing, furious. An unashamed masochist in the performance space. Seeing that was huge for me.

What is the role of fantasy and narrative in your performances?

I think this is one the biggest parallels shared by kink and performance. Both involve world building, creating an emotional arc, a beginning, middle and end. When I plan either a BDSM scene or a performance, I ask myself: who do I want to be? How do I want to feel? What do I want to become? And what about my play partner or my audience? How do I want them to feel, how do they want to feel?

I don’t use fantasy to escape reality, I use it to pierce through it.

I also think, with performance in particular, even though it’s relational, it’s also kind of one-sided. So, there exists another fantasy — the one that’s being projected onto me by the viewer. Especially as a masochist doing pain performances, there are so many stories that people might tell themselves to make sense of what they’re seeing, and I intentionally leave that space open. I like to act as a mirror, and invite people to interrogate the way that they view me. Do I look submissive, broken, brave, dangerous? Why? What tells them that? I want them to leave asking not just who I was, but who they became when they looked at me.

In what ways is transformation important to you?

I believe so much in transformation, the power to transform is so human and ancient. I first learned transformation as a means of survival, when I was young. To grow, become something else, expand beyond your environment or your upbringing, or delve into fantasies like games and books. It’s how you hold what’s unbearable, and start to move towards discovering what’s possible.

Transformation isn’t just about survival — it’s also play, eroticism, surrender, ritual. And it’s political and communal too. Transforming ourselves lets us transform our relationships, our communities, how we hold each other, how we create space for bigger change. My work offers models for change that we can use to transform all things in our lives.

How are pain and surrender in dialogue with each other during your performances?

Pain is a language your body uses to communicate with you. It’s not an inherent evil to be avoided — it’s a language of care. When we can enter into dialogue with pain, with our bodies, we can develop such a deep and meaningful relationship with ourselves. Pain is the invitation. Surrender is how we can respond. Surrender is the willingness to endure. So, pain and surrender are literally in dialogue during a performance. I introduce pain through a needle in my flesh, and surrender to the experience, and the rest is a dance — playing with the tension of each so I can find a challenging and beautiful kind of harmony between the two.

Arcadia Molinas is the online editor of Worms.